Natura Inmotus Perpetuo

“I want to signify and understand the true cosmographies(…) of the Indies, islands and the mainland of the Ocean Sea(…) where innumerable and very great kingdoms and provinces are included; of so much admiration and wealth(...)”

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo,

Historia general y natural de las Indias, Tomo I.

The first half of the 16th century meant a true paradigm shift for men on the European continent. After the first voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492, the number of these subjects changed dramatically. The known world to that day extended to borders never seen before, there was an encounter of diverse worlds, which were under the domain of the great European courts, especially the Crown of Castile and the kingdom of Portugal. Faced with the impossibility of traveling to the New World, the Hispanic kings sent a series of cosmologists, naturalists and presbyters to exploit every corner of that new and mysterious lands that existed beyond the horizon.

The Plus Ultra, the indomitable regions past the famous columns of Hercules, were home to countless villages, species of colorful animals and botanical specimens that undoubtedly surpassed the imagination of these men. Among those travelers who launched overseas, it is particularly striking the case of Francisco Hernández de Toledo, who made the first "scientific expedition" throughout the region of New Spain during the 1570s.

Hernández launched to the field to study the "natural things" of the Indias, almost immediately, and established his base of operations in Mexico City. After exploring the regions near the viceregal captial, he went to the tropical area (known as tierra caliente, land of unyeilding heat) near Temascaltepec, until he reached Quaunhnáhuac, the current Cuernavaca, and extended his work through its surroundings including: Tepoztlán, Yautepec and Oaxtepec, regions in which which he gathered an impressive number of botanic specimens and some insects.

Hernández's descriptions of the land, that currently is the State of Morelos, display an incredible astonishment. In addition to the scientific descriptions, the author points out almost idyllic landscapes, typical of the Indian exuberance that they imagined in the royal court. In regions like Oaxtepec, a place where a hospital had been established in which "(...) (one could find) gathered the most beautiful flowers and plants of the whole territory (...)" whose surroundings "(...) were very happy clean fountains and rivers that watered the forest everywhere (...) "

The great Franciscan and Dominican convents, the hospital of Oaxtepec and the rich orchards of Cuernavaca witnessed one of the most important scientific activities of the 16th century. The specimens compiled by Hernández in the current Morelos made up almost tweny-five per cent of the more than a thousand foliaes expressed and richly drawed then the naturalist sent to Spain (Spanish Crown) at the end of his trip.

The destiny of the books that comprised the work had a journey of its own in which the documents practically disappeared up until the twentieth century. Similar to the texts themselves, the lush plants and the hundreds of specimens of anmiales suffered a random destiny, and in some cases the extinction and destruction of those natural paradises.

As a tribute to the work of Hernández and that lost nature, I present a photographic project in which some specimens of the insects and plants of Cuernavaca- that still persist in the XXI, are still portrayed in still life. If in the Natural History we find the vestiges of the natural wonders described by Hernández almost five centuries later, the photographs emulate the colored sheets that accompanied the text. However, these contemporary pics are characterized by lack of color for they are in B&W. The photographic project aims to create a new kind of Natural History of Morelos of the 21st century, a damaged land yet where you can find the last refuges of the lush nature that Hernández encountered in the sixteenth century.

Rodrigo Gordoa de la Huerta is a historian specialized in colonial history of Mexico,

He teaches at the National University

and the Mora Institute in Mexico City.

Media

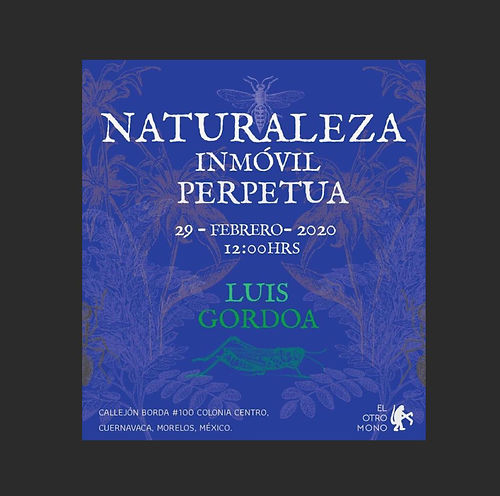

Expo El Otro Mono

Flyers